In Bangladesh, March 25 is marked as Genocide Day, the anniversary of the start of the Pakistani army’s brutal campaign of suppression in 1971 that claimed some three million lives. There is now a powerful campaign for international recognition that the mass murders, rapes and torture were an act of genocide against the Bengali people. It took an important step forward in Brussels on this year’s anniversary, with a special event organised by the Bangladesh Embassy, writes Political Editor Nick Powell.

The Bangladesh genocide was one of the worst such events in human history. The killings, rapes and other atrocities became widely known at the time, with widespread popular support around the world in 1971 for the struggle for freedom of the people of what was then East Pakistan. Yet, just as governments at the time were slow to recognise the democratic legitimacy of a free Bangladesh, the international community has still not acknowledged the genocide.

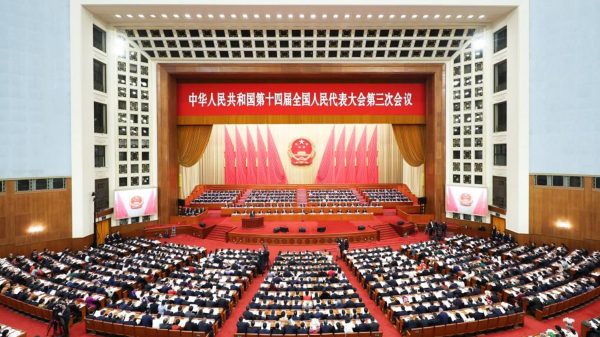

At the Brussels Press Club, diplomats, journalists, academics, politicians and members of the Bangladeshi community in Belgium gathered to hear a powerful case for recognition of the genocide and for an apology from Pakistan for the actions of its military and local collaborators. They heard testimony from scholars and survivors, who believe that the case for acknowledging genocide has to be made, even if it should be obvious.

Professor Gregory H Stanton, the founding president of Genocide Watch warned that the recognition is as essential to healing “as closing an open wound”. He observed that his own government, in the United States, is yet to recognise the Bangladesh genocide. The American government was equally silent in 1971, unwilling to offend its Cold War ally in Pakistan.

Prof. Stanton argued that as well as recognising the genocide itself, the US should recognise that stance taken by its Consul General in Dhaka, Archer Blood, who destroyed his diplomatic career by forwarding to the State Department a note signed by numerous American officials who would not close their eyes to what was happening.

“Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy”, they wrote. Even in 2016, as the Bangladesh Ambassador, Mahbub Hassan Saleh, told the audience in Brussels, President Nixon’s Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, would only concede that Pakistan had “resisted with extreme violence” and committed “human rights violations”.

As the Ambassador pointed out, Pakistan’s military was waging war not just against the Bengali people but against the man who had won such an overwhelming election victory in East Pakistan that he was the legitimate Prime Minister of the entire Pakistani state, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It gave him the legal basis to declare independence, though he waited until the last moment when the Pakistan military launched its genocidal war.

Brave reporting, notably by Anthony Mascarenhas, brought the truth to the world. His account in the Sunday Times was simply headlined ‘Genocide’. His quotation from a Pakistani commander was read out at the Brussels Press Club by Professor Tazeen Mahnaz Murshid. “We are determined to rid East Pakistan of the threat of cessation, once and for all, even if it means killing two million people and ruling it as a colony for 30 years”.

For Prof. Murshid, herself a genocide survivor, this brought out the nature of this crime against humanity. It was an attempt to impose a final solution, a dehumanising culture of impunity supported by the moral bankruptcy of the international community. The exception on the world stage was India, which housed millions of refugees and suffered ‘pre-emptive’ Pakistani raids on its airfields. India finally sent its troops into East Pakistan, ensuring victory for the liberation struggle and the birth of Bangladesh.

Further proof of genocidal intent was the targeting of political, intellectual and cultural leaders. In a short, moving statement Shawan Mahmud, the daughter of the martyred lyricist, composer and language activist Alaf Mahmud relived her memories of her father’s death.

Another contributor was Irene Victoria Massimino, from the Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention. For her, an important part of preventing genocide lies in the recognition of the genocide, the acknowledgement of victims and their sufferings, in accountability and justice. And in his address, Paulo Casaca, founder of the South Asia Democratic Forum, regretted that Pakistan is yet to apologise for the sinister crimes committed by its military junta in 1971.

Ambassador Saleh, in his concluding remarks, observed that recognition of the Bangladesh genocide “would do justice to history” and offer some solace to the survivors and to the families of the victims. “How could there be a closure without a recognition by the world and an apology from the perpetrators, that is the Pakistan military?”, he asked.

He added that his country had “no reservations or hatred” about the people of any country, including Pakistan, but it was only fair to say that Bangladesh deserved an apology. He expressed the hope that recognition of the Bangladesh genocide would find reach and understanding with a wider international audience. With time, he hoped, a resolution supporting recognition of the genocide would be passed by the European Parliament.