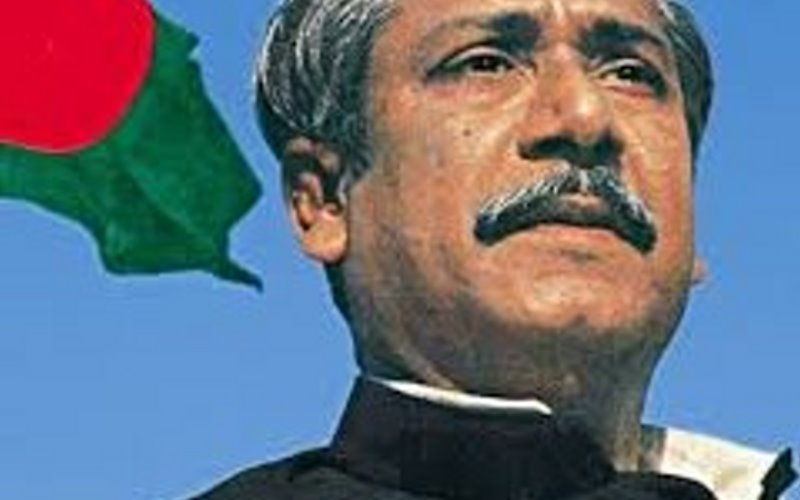

As the people of Bangladesh observe one more anniversary of their triumph on the battlefield in 1971, it is only proper that we travel back to the time when the bandwagon of freedom was beginning to move inexorably toward its destined goal- writes Syed Badrul Ahsan.

We speak of those tumultuous days of December 1971. We will always reflect on the nature of that great victory that transformed us into a free nation, into masters of our destiny as it were. We will celebrate again as dawn breaks on 16 December this year. We will mourn the three million of our compatriots who gave their lives for the rest of us to live in liberty.

And, to be sure, we will not forget the events and incidents which have forever etched December 1971 in our souls. There is that terse announcement made by Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi late in the evening on 3 December, when she informed the world that Pakistan’s air force had carried out raids on Indian air bases and that the two countries were now at war. Three days later, we cheered when India accorded official recognition to the fledgling state of Bangladesh. It was a sign that our Indian friends would wage war against Pakistan, just as the Mukti Bahini was waging war against Pakistan, until Bangladesh stood liberated. In the event, as many as twenty thousand Indian soldiers lost their lives for a cause that was ours. It is a debt we cannot ever repay.

Interesting, often bizarre things were happening in Pakistan in the run-up to 16 December. On the same day that General Yahya Khan ordered an air strike on Indian bases, he appointed the Bengali Nurul Amin prime minister of Pakistan. The appointment was misleading, intended to convey the impression before the world that the regime was on its way to transferring power to elected politicians. Ironically, the majority party emerging from the 1970 elections was then on its way to creating Bangladesh in the crumbling province of East Pakistan. And the man who would have been Pakistan’s prime minister, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was in solitary confinement in the Punjab town of Mianwali.

Besides appointing Nurul Amin as prime minister, Yahya decreed that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, chairman of the Pakistan People’s Party, would be deputy prime minister and foreign minister. In a few days, Bhutto would be sent off to the United Nations, where he would rant on the ‘conspiracies’ being hatched against his country. Bhutto would, in theatrical fashion, tear up a sheaf of papers which he said was a proposed Security Council resolution and stalk out of the UNSC chamber. In the days following the outbreak of war on 3 December, Indian forces would march deep into what was yet known as West Pakistan. In the east, the Mukti Bahini and the Indian army would continue their relentless march into a shrinking East Pakistan.

The Pakistan air force was destroyed on the ground in East Pakistan by the Indians right at the beginning of the conflict. But that did not prevent General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, commander of Pakistan’s forces, from telling foreign newsmen at the Intercontinental Hotel that the Indians would take Dhaka over his dead body. In the end, when Dhaka fell, Niazi was very much alive, though not kicking.

A few days before Pakistan’s surrender at the Race Course, Khan Abdus Sabur, once a powerful minister of communications in Field Marshal Ayub Khan’s regime and in 1971 a prominent collaborator of the Pakistan army, told a pro-Islamabad meeting in Dhaka that if Bangladesh came into being, it would be as an illegitimate child of India. Other collaborators, especially the ministers in A.M. Malik’s puppet provincial government, promised to crush India and the ‘miscreants’ (their term for the Mukti Bahini) through the mighty Pakistan army.

On 13 and 14 December, the murder squads of the Jamaat-e-Islami — al-Badr and al-Shams — began abducting Bengali intellectuals as their final, desperate blow to the Bangladesh cause before Pakistan came crashing down in this land. Those intellectuals would never return. Their mutilated corpses would be discovered at Rayer Bazar two days after liberation.

In December 1971, such prominent Bengali collaborators of the Yahya Khan junta as Ghulam Azam, Mahmud Ali, Raja Tridiv Roy, Hamidul Haq Chowdhury and, of course, Nurul Amin would be stranded in West Pakistan. Ghulam Azam would return to Bangladesh on a Pakistani passport in 1978, stay on despite the expiry of his visa and die a convicted war criminal decades after Bangladesh’s liberation. Chowdhury would come back and reclaim his newspaper. Nurul Amin would serve as Pakistan’s vice president under Z.A. Bhutto, with Tridiv Roy and Mahmud Ali joining Pakistan’s cabinet as ministers. Roy would subsequently be Pakistan’s ambassador to Argentina.

Only days before his capitulation, General Niazi was summoned to the Governor’s House (today’s Bangabhaban) by Governor A.M. Malik, who patronisingly told him that he and his soldiers had done their best in the most difficult of circumstances and ought not to feel upset. Niazi broke down. As Malik and the others present consoled him, a Bengali servant came in with tea and snacks for everyone. He was immediately howled out of the room.

Once outside, he told his fellow Bengali servants, ‘The sahibs are crying inside.’ A few days later, as Indian jets bombed the Governor’s House, Malik and his ministers took refuge in a bunker, where the governor, his hands shaking, wrote out a letter of resignation to President Yahya Khan. Once that was done, he and other leading collaborators were escorted, under UN supervision, to the Intercontinental hotel, which had been declared a neutral zone.

And then liberty came … on the declining afternoon of 16 December.

Fifty-two years on, we remember. The glory that was ours shines brighter than ever before.

The writer Syed Badrul Ahsan is a London-based journalist, author and analyst of politics and diplomacy.