By Nick Powell in Panama

The World Health Organisation’s conference in Panama on tobacco control has been mired in disagreement and would not even condemn a delegate who spread the false allegation that vaping causes cancer. Despite this, there is every danger that the European Union will continue to toe the WHO’s line and conflate cigarettes with products that enable smokers to switch to much less dangerous substitutes, writes Political Editor Nick Powell.

The European Commission is proud of what it calls the Brussels effect, that when the EU makes regulations on the safety of consumer products much of the world follows suit, so that manufacturers can access the European market. But tobacco control has become a major exception, with Europe’s smokers at risk of being denied the most effective ways of giving up cigarettes, as the EU is not a leader but a follower of the World Health Organisation’s policies.

Here in Panama, a source told me that the delegation from the Commission’s Directorate General for Health and Food Safety, DG SANTE, is agreeing to proposals well beyond its mandate. They have not even mentioned Sweden, a member state that thanks to oral nicotine products banned in the rest of the EU has achieved the lowest cigarette consumption in the world.

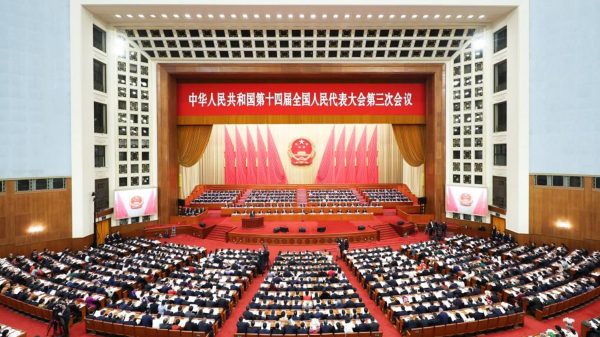

The WHO’s tenth conference of the parties (COP10) to its Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has spent the week in heavily defensive mode. Like many journalists, I was refused accreditation but that made little difference as the conference voted to exclude the press. That was shortly after the organisers cut off the microphone of a delegate who had the temerity to suggest that the priority should be harm reduction.

It might seem an obvious point that harm reduction -getting people to stop smoking cancer-causing cigarettes- should be the focus but it’s hard to overstate how heretical that view has become. Science has gone out of the window and when another delegate posted a mocked-up picture of a ‘cancer flavour’ vape it went viral.

Switching to vaping is an excellent way for cigarette smokers to eliminate the risk of developing cancer as a result of satisfying their craving for nicotine. It’s inhaling tobacco smoke (or indeed any smoke) that causes cancer.

The conference organisers took no action over this incident. They were too busy getting the Panamanian authorities to stop consumer activists handing out leaflets to delegates urging them to support e-cigarettes and other non-combustible alternatives to smoking.

It is probably too much to hope that these embarrassing episodes will cause DG SANTE to doubt the wisdom of following the WHO’s approach so closely. Rather it is legal action in the member states against the Commission going beyond its mandate that is giving its policies some urgently needed scrutiny.

A delegated directive to member states on how to regulate flavoured heated tobacco products created a product definition that simply did not exist in the Tobacco Products Directive agreed by the EU’s co-legislators, the Parliament and the Council. It tried to treat in the same way as cigarettes much safer non-combustible alternatives. This was at best confusing for consumers and at worst an attempt to regulate beyond the mandate given to the Commission by the co-legislators.

This apparent power grab was referred to the European Court of Justice by the Irish High Court last year. Two companies successfully challenged an attempt to ban flavoured heated tobacco products that were exempted under the original EU legislation. Since then, the Belgian Ministry of Health has suffered a similar but even more comprehensive defeat when the country’s supreme court, the Council of State, annulled a decision to treat a well-known brand of heated tobacco products not as smoke-free alternatives to cigarettes but as if they were in fact cigarettes.

This would have had the nonsensical effect of requiring the manufacturer to include pictures on the packets illustrating health risks that are greatly reduced or completely avoided by switching to these products instead of smoking cigarettes. But no attempt by the Commission to clarify the situation can be expected before the European election in June and the subsequent appointment of a new college of commissioners.

It seems that word has come down from Ursula von der Leyen to postpone proposals that are likely to prove highly controversial with the member states and with MEPs. However, the argument has only been delayed and no doubt the DG SANTE delegation will return from Panama enthused to make a new attempt to enforce the WHO’s approach.

The WHO has urged countries to adopt six tobacco control measures known by the acronym MPOWER:

Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies.

Protecting people from tobacco smoke.

Offering help to quit tobacco use.

Warning about the dangers of tobacco.

Enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.

Raising taxes on tobacco.

Monitoring, protecting and warning are uncontroversial and tobacco advertising has long been banned in most countries. However, as has been seen in France, raising taxes can have unintended consequences as the profit margins increase for criminal gangs who illicitly trade in unregulated products and don’t pay a cent in tax. It has turned France into the country where half of all the EU’s illicit cigarettes are smoked.

Offering help to quit tobacco use is good as far as it goes but it fails to specify what that help should be; still less does it insist on providing help that actually works. Several experts who travelled to Panama to point out such inconvenient truths found themselves ignored and excluded from COP10.

One harm reduction advocate, Mark Oates, observed that the WHO had become more concerned with stigmatising both smokers and vapers than with actually reducing cigarette-smoking. He queried why Sweden, the only EU country to have got cigarette smoking down to the target of less than 5% of the population, is considered a failure by the WHO but Australia a success. Sweden is disliked by the WHO because of the popularity of its traditional tobacco product, snus, which is far less harmful because it does not involve smoking.

Australia is rated more highly by the WHO, said Mark Oates, because it has concentrated on trying to make all forms of tobacco consumption less socially acceptable. Cigarettes, which are mostly consumed by socially disadvantaged groups, are highly taxed and legal vapes are hard to obtain. But Australia has also demonstrated how the black market can and will supply illegal and unregulated products, even in an island country with a greater chance of limiting cross-border smuggling than almost anywhere else on earth.

Martin Cullip, who is international fellow at the Taxpayers Protection Alliance’s Consumer Centre, argued that even when people who have never smoked take up vaping, it should be considered a success if they would have otherwise turned to cigarettes. He said the WHO had pre-briefed delegates that there was no evidence that e-cigarettes had reduced smoking, a conclusion that could only be reached by excluding all serious scientific research.

Public wellbeing advocate Chris Snowdon added that unfortunately there was also a mountain of bad science about e-cigarettes. Politicians are expected to be more impressed by quantity than quality -and they usually are. “The amount of nonsense out there is effectively infinite”, he observed.

He pointed to the example of the UK’s proposed ban on disposable vapes, where a report asking what would happen to 2.6 million British adult users was drowned out. Mark Oates said Britain’s National Health Service currently supplies disposable vapes to people with mental health issues. These are especially designed to prevent their use in self-harm but the manufacturer has been told that the contract will not be renewed.

Tim Andrews, from the Tholos Foundation in the USA, said the spread of bad science in America had reached the point where even doctors often wrongly thought that smoking cigarettes is less dangerous than vaping. He cited the case of a mother who gave her children cigarettes to stop them vaping.

The problem, he argued, is that regulators find it impossible to accept that not only has their strategy not worked but that the market had found the solution in nicotine products that do not involve smoking. He could understand their reluctance to admit that they were wrong but his sympathy has run out because millions of lives are at stake.

A consumer advocate from South Africa, Kurt Yeo, wondered if COP10 had got into a bit of a panic because the WHO knows that the science is against it and time is running out for its policies. It might just be the right moment for the EU to move away from its unusually subservient position on how to eliminate cigarette smoking.